If you are already using Redis in your stack, you probably don’t need the operational overhead of setting up Kafka.

Now, you might think I’m suggesting Redis Pub/Sub. I am not. While Pub/Sub is great for real-time notifications, it falls short for critical data processing. This article is about tweaking Redis Streams to build a robust, persistent pub/sub architecture that mimics the reliability of Kafka, using the tools you already have.

Why build on top of Redis Streams instead of using standard Pub/Sub?

1. Solves the “Fire and Forget” Problem (Durability) Redis Pub/Sub acts like a live radio broadcast. If your service is down or crashes due to a network error, it misses the message forever. There is no retry mechanism. Redis Streams, however, acts like a log file . It persists the message. If your consumer crashes, the message waits safely in Redis until your service comes back online to process it.

2. True Load Balancing (Consumer Groups) Standard Pub/Sub broadcasts every message to every subscriber (Fan-out). If you have 5 instances of your backend running, they will all receive the same “Process Payment” message, leading to duplicate charges. Redis Streams supports Consumer Groups. This allows you to distribute the load: Redis ensures that if Instance A picks up Message 1, Instance B will automatically move on to Message 2.

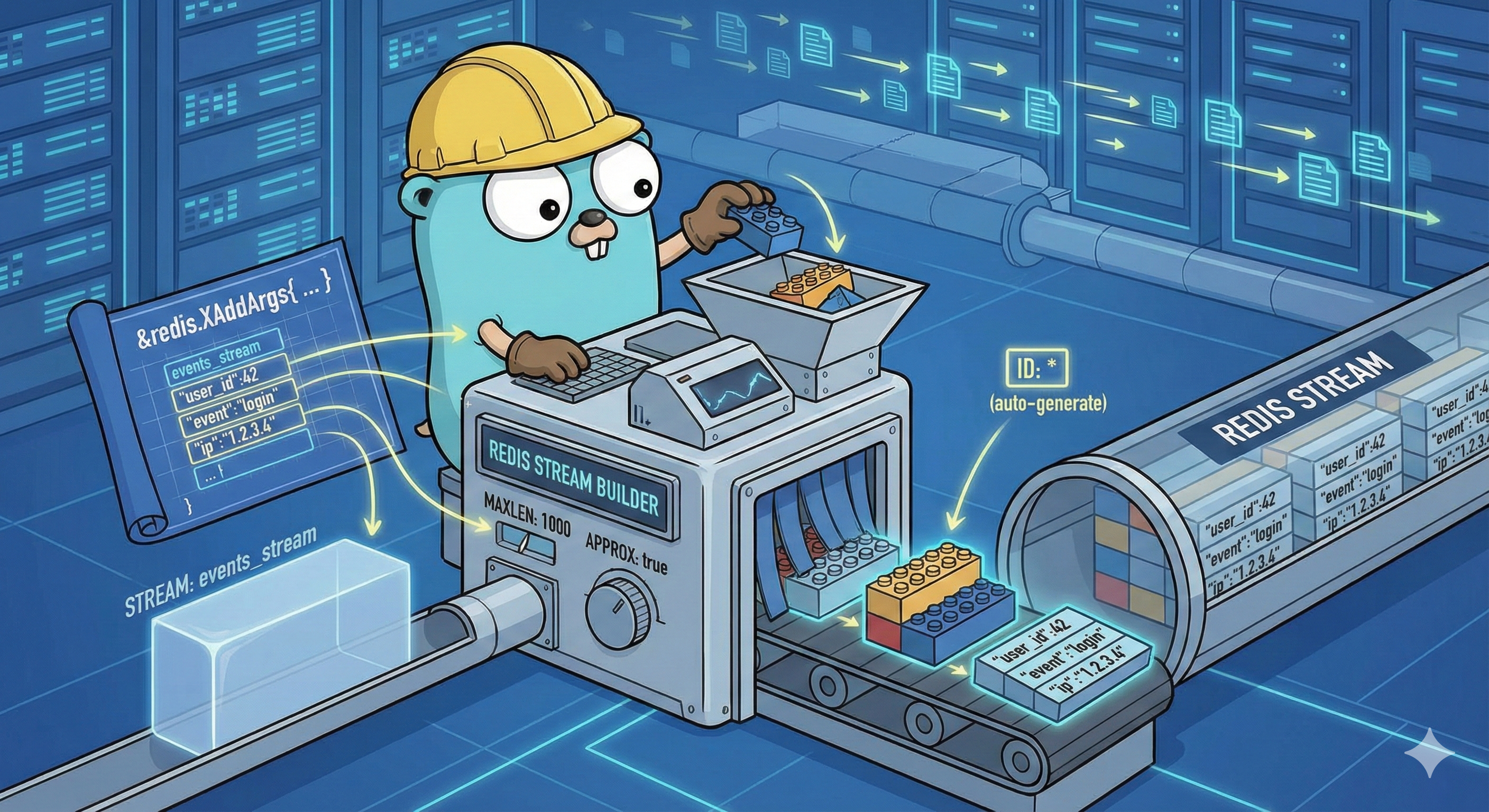

Let’s look at how to implement the three core components in Go: The Producer, The Consumer Group setup, and The Worker Loop.

One of the most annoying things about Redis Streams is that if you try to create a Consumer Group that already exists, Redis throws an error (BUSYGROUP). If you are deploying this in Kubernetes, your pods might restart frequently. You don’t want your app to crash just because the group is already there.

We solve this with an EnsureGroup method. It checks if the stream exists, creates it if it doesn’t, and gracefully handles the BUSYGROUP error.

func (s *StreamManager) EnsureGroup(ctx context.Context) error {

// 1. If the stream doesn't exist, create it AND the group

exists, _ := s.client.Client.Exists(ctx, s.stream).Result()

if exists == 0 {

return s.client.Client.XGroupCreateMkStream(ctx, s.stream, s.group, "$").Err()

}

// 2. If stream exists, try to create the group

err := s.client.Client.XGroupCreate(ctx, s.stream, s.group, "$").Err()

if err != nil && err.Error() != "BUSYGROUP Consumer Group name already exists" {

return fmt.Errorf("failed to create group: %w", err)

}

return nil

}Note the $ symbol: This tells Redis to only deliver messages that arrive after the group is created. If you want the consumer to process old history, use 0

The Consumer Loop

This is where Redis Streams differs entirely from Pub/Sub. In Pub/Sub, you listen on a socket. In Streams, you pull data.

However, we don’t want to hammer Redis with requests (while true: read()). We want to wait until data is available. We use XREADGROUP with the Block argument.

func (s *StreamManager) Consume(ctx context.Context, consumerName string, handler func(Message) error) error {

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err()

default:

// "Block" tells Redis: Wait 2 seconds for data before returning empty.

streams, err := s.client.Client.XReadGroup(ctx, &redis.XReadGroupArgs{

Group: s.group,

Consumer: consumerName,

Streams: []string{s.stream, ">"}, // ">" means "Give me new messages"

Count: 10,

Block: 2 * time.Second,

}).Result()The > character is the implementation detail here. It tells Redis: “Give me messages that have never been delivered to any other consumer in this group.” This is how we achieve load balancing across multiple worker instances.

The “At-Least-Once” Guarantee (The ACK)

This is the most critical logic flow. In a “Fire and Forget” system, the message is gone the moment it leaves the producer. In our system, the message enters a “Pending” state when we read it.

It stays pending until we explicitly tell Redis we are done via XACK.

for _, msg := range stream.Messages {

// 1. Process the message (Execute Business Logic)

if err := handler(message); err != nil {

log.Printf("Error processing message: %v", err)

continue

}

// 2. Only ACK if processing was successful

if err := s.AcknowledgeMessage(ctx, msg.ID); err != nil {

log.Printf("Error acknowledging message: %v", err)

}

}By strictly ordering the operations—Process, then ACK—we ensure that if the pod crashes during processing, the message is not lost. It remains in Redis, waiting to be claimed by another consumer (using XAUTOCLAIM, which we can cover in a future advanced article).

Putting It All Together

Finally, let’s wire everything up in our main.go.

We need to do three specific things here to make this production-ready:

- Ensure the Consumer Group exists before we start (so we don’t crash on the first run).

- Run the Consumer in a background Goroutine so it doesn’t block the main thread.

- Listen for OS Signals to shut down gracefully. If we just kill the app, we might leave messages in a “half-processed” state.

func main() {

// 1. Initialize the connection

rdb := redis.NewClient(&redis.Options{

Addr: "localhost:6379",

})

store := &RedisStore{Client: rdb}

// Initialize our Manager

streamManager := NewStreamManager(store, "orders_stream", "payment_processors")

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

if err := streamManager.EnsureGroup(ctx); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to init stream group: %v", err)

}

// 3. Run the Consumer in th*e Background*

go func() {

err := streamManager.Consume(ctx, "worker-1", func(msg Message) error {

log.Printf("Processing Message: %v", msg.Values)

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

return nil

})

if err != nil && err != context.Canceled {

log.Printf("Consumer died: %v", err)

}

}()

}At the end of the day, this project was largely an experiment. I wanted to see if I could mimic the reliability of Kafka without actually having to deploy Kafka.